This morning, I am listening to Anton Bruckner’s Symphony No. 5 in B Flat Major (WAB 105), nicknamed “Pizzicato Symphony” or “Tragic,” interpreted by the legendary German conductor and composer Wilhelm Furtwangler (1886-1954).

This morning, I am listening to Anton Bruckner’s Symphony No. 5 in B Flat Major (WAB 105), nicknamed “Pizzicato Symphony” or “Tragic,” interpreted by the legendary German conductor and composer Wilhelm Furtwangler (1886-1954).

His orchestra is equally legendary, the Berliner Philharmoniker or – as it’s more commonly known – the Berlin Philharmonic.

From the entry about him on Wikipedia,

Wilhelm Furtwängler (January 25, 1886 – November 30, 1954) was a German conductor and composer. He is considered to be one of the greatest symphonic and operatic conductors of the 20th century.

Furtwängler was principal conductor of the Berlin Philharmonic between 1922 and 1945, and from 1952 until 1954. He was also principal conductor of the Gewandhaus Orchestra (1922–26), and was a guest conductor of other major orchestras including the Vienna Philharmonic.

He was the leading conductor to remain in Germany during the Second World War, although he was not an adherent of the Nazi regime. This decision caused lasting controversy, and the extent to which his presence lent prestige to the Third Reich is still debated.

Furtwängler’s conducting is well documented in commercial and broadcast recordings and has contributed to his lasting reputation. He had a major influence on many later conductors, and his name is often mentioned when discussing their interpretive styles.

Of Furtwangler’s style of conducting, the entry on Wikipedia reads,

Conducting style

Furtwängler had a unique philosophy of music. He saw symphonic music as creations of nature that could only be realised subjectively into sound. Neville Cardus wrote in the Manchester Guardian in 1954 of Furtwängler’s conducting style:

He did not regard the printed notes of the score as a final statement, but rather as so many symbols of an imaginative conception, ever changing and always to be felt and realised subjectively…Not since Nikisch, of whom he was a disciple, has a greater personal interpreter of orchestral and opera music than Furtwängler been heard.

And the conductor Henry Lewis:

I admire Furtwängler for his originality and honesty. He liberated himself from slavery to the score; he realized that notes printed in the score, are nothing but SYMBOLS. The score is neither the essence nor the spirit of the music. Furtwängler had this very rare and great gift of going beyond the printed score and showing what music really was.

Many commentators and critics regard him as the greatest conductor in history. In his book on the symphonies of Johannes Brahms, musicologist Walter Frisch writes that Furtwängler’s recordings show him to be “the finest Brahms conductor of his generation, perhaps of all time”, demonstrating “at once a greater attention to detail and to Brahms’ markings than his contemporaries and at the same time a larger sense of rhythmic-temporal flow that is never deflected by the individual nuances. He has an ability not only to respect, but to make musical sense of, dynamic markings and the indications of crescendo and diminuendo[…]. What comes through amply… is the rare combination of a conductor who understands both sound and structure.” He notes Vladimir Ashkenazy who says that his sound “is never rough. It’s very weighty but at the same time is never heavy. In his fortissimo you always feel every voice…. I have never heard so beautiful a fortissimo in an orchestra”, and Daniel Barenboim says he “had a subtlety of tone color that was extremely rare. His sound was always ’rounded,’ and incomparably more interesting than that of the great German conductors of his generation.”

A little background on the Berlin Philharmonic, from its entry on Wikipedia, is in order here:

The Berlin Philharmonic (German: Berliner Philharmoniker), is an orchestra based in Berlin, Germany and is consistently ranked as one of the best orchestras in the world.

In 2006, ten European media outlets voted the Berlin Philharmonic number three on a list of “top ten European Orchestras”, after the Vienna Philharmonic and the Royal Concertgebouw Orchestra, while in 2008 it was voted the world’s number two orchestra in a survey among leading international music critics organized by the British magazine Gramophone (behind the Concertgebouw). The BPO supports several chamber music ensembles.

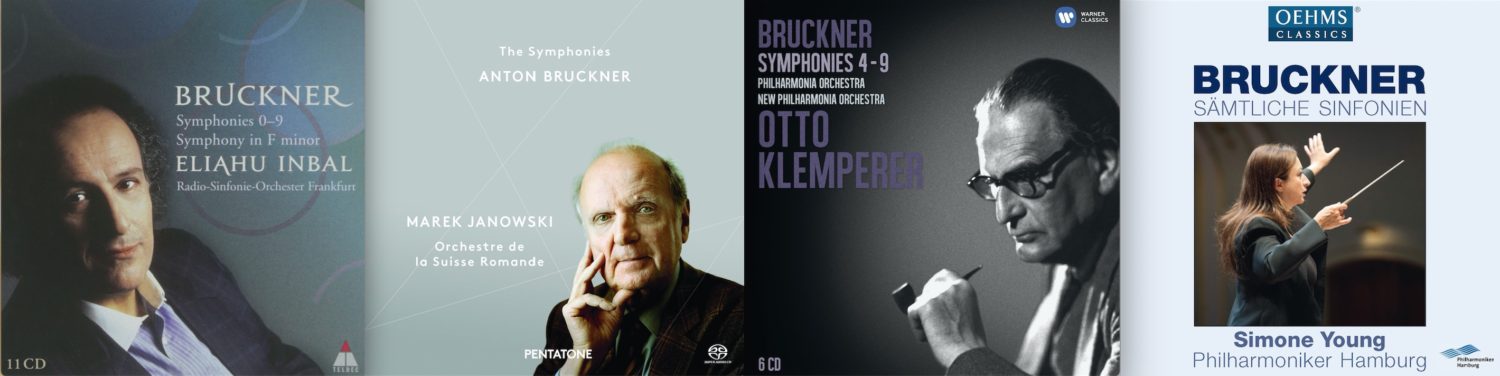

Given the historical nature of this performance (it was recorded 75 years ago!), and despite the fame of Furtwangler and the Berlin Philharmonic, I don’t expect to hear something akin to what’s found in the Marek Janowski box set released by Pentatone. This won’t be an eargasm. More than likely, this will sound like two tin cans and a string with a third string leading to a reel-to-reel tape machine.

I’m prepared for that.

But you know how this works.

First, the objective stuff.

Then, my opinion of the performance and box set and liner notes, etc.

The objective stuff:

Bruckner’s Symphony No. 5 in B Flat Major (WAB 105), composed 1875–1876

Bruckner’s Symphony No. 5 in B Flat Major (WAB 105), composed 1875–1876

Wilhelm Furtwangler conducts

Furtwangler used the “1878 Haas Edition,” according to the liner notes.

Berlin Philharmonic plays

The symphony clocks in at 68:50

This was recorded in (probably) Berlin, Germany, on October 28, 1942 (!)

Furtwangler 56 was when he conducted it

Bruckner was 52 when he finished composing it (the first time)

This recording was released on the Music & Arts Programs of America label

From the liner notes, written by John Ardoin,

The Fifth Symphony is one of Bruckner’s most striking and individual works. There is an overriding cyclic sense to it, for the out movements begin alike as do the inner ones, while the second and third movements also contain the germ of the first and fourth. Beyond that there is thematic cross-pollination throughout that results in an exceptional economy of thought and action.

Huge thrusts of energy are expelled in each performance of the Fifth Symphony…

Bruckner wrote his symphonies in four movements. The time breakdown of this one (Symphony No. 5 in B Flat Major), from this particular conductor (Furtwangler) and this particular orchestra (Berliner Philharmoniker) is as follows:

I. Adagio — Allegro……………………………………………………………………..19:07

II. Adagio – Sehr langsam. (Very slowly)……………………………………..15:37

III. Scherzo – Molto vivace…………………………………………………………..11:58

IV. Finale (Adagio) — Allegro moderato……………………………………..21:52

Total Time: 68:50

Okay. Now, here are the subjective aspects:

My Rating:

My Rating:

Recording quality: 3

Overall musicianship: 5

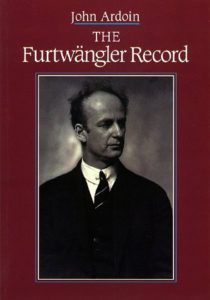

CD liner notes: 4 (thin booklet – in English only – that’s an excerpt from John Ardoin’s book The Furtwangler Record published in 1994)

How does this make me feel: 5

I’m listening to something akin to a time capsule, a recording from an age so far removed from our own that the historicity of it probably overshadows its actual value.

But, for me, therein lies its beauty…and greatest strength.

Our local museum features a section called Gaslight Village. It’s a couple of rooms designed to look like turn-of-the-century scene from early Grand Rapids. Cobblestone streets. A horse-drawn carriage. An old automobile. Shops that look like something from Little House on the Prairie.

I could sit for hours in that section and imagine what life was like for the people who worked in and frequented those shops.

I get that same feeling listening to this recording.

It’s majestic. Transcendent. Emotional. Engaging.

As I listen to this, I am acutely aware that I am an eavesdropper to the early 1940s. In Berlin. Which means Nazism was in full swing. In fact, Berlin was ground zero for Hitler’s campaign to dominate the world.

Yet, at the same time, here’s this resplendent recording by the Berlin Philharmonic, conducted by Wilhelm Furtwangler.

I can’t really say any one movement stood out to me, although I did take note of the pizzicato of the first movement, around the 4:30 and 13:00 marks.

Also, I must admit that the Scherzo to Bruckner’s Fifth isn’t as appealing to me as the Scherzo in his previous symphonies. This one doesn’t leap out of my earbuds, grab me by the lapels, and slap me across the face. It doesn’t have the power or cleverness of his other Scherzos. (Although I like the melody and interplay between the instruments in the first couple of minutes.)

Overall, this is a fascinating recording, one with just the right amount of ambient noises (coughing, shuffling, turning pages, shifting in one’s seat, etc.)

NOTE: the last couple of minutes (starting at 19:00) of the Finale are some of the most dynamic and powerful I’ve ever heard. The orchestra ramps up to a fevered pitch that practically drowns out the microphones, pushes them in to the red. (“Buries the needle as Dr. Raymond Stantz says in Ghostbusters.”) Seriously, check out 19:41 to 19:52. It’s like an explosion of sound.

Unlike Bruckner’s Fourth conducted by Furtwangler (Day 20), I could recommend this to a Bruckner newbie.

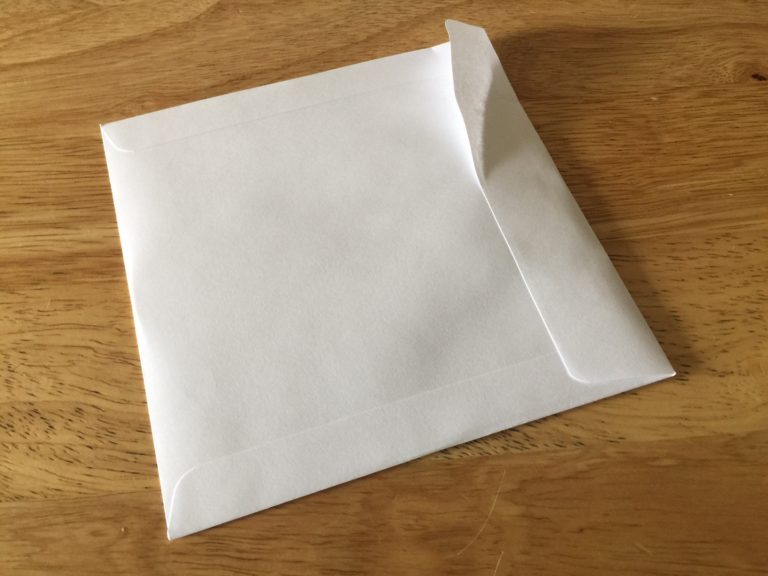

There is one niggling problem I have with the Furtwangler box set that I forgot to mention the first time I cracked it open: The paper sleeves the CDs come in are sealed.

Yes. Sealed.

Which means you have to tear them open to get the CD out.

Whose bright idea was that?