My “office” this morning is a favorite bagel place called Big Apple Bagels.

I’m a sucker for bagels, especially to enjoy while I listen to music, sip coffee, and ponder the world.

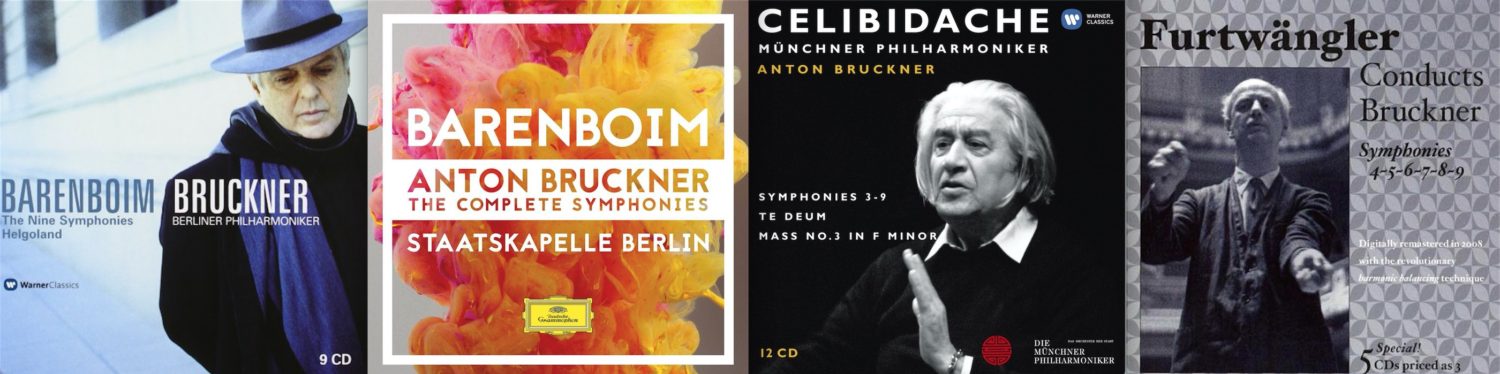

My musical selection this morning is Anton Bruckner’s Symphony No. 7 in E Major (WAB 107) interpreted by the legendary German conductor and composer Wilhelm Furtwangler (1886-1954).

My musical selection this morning is Anton Bruckner’s Symphony No. 7 in E Major (WAB 107) interpreted by the legendary German conductor and composer Wilhelm Furtwangler (1886-1954).

His orchestra is equally legendary, the Berliner Philharmoniker or – as it’s more commonly known – the Berlin Philharmonic.

I’m not going to repeat the background on Maestro Furtwangler, although I do suggest you read up on him.

I first encountered Wilhelm Furtwangler on Day 20, Symphony No. 4.

Then again on Day 28, Symphony No. 5.

Then again on Day 36, Symphony 6.

The first link above will give you a good idea who the man was and what he was known for regarding his conducting style.

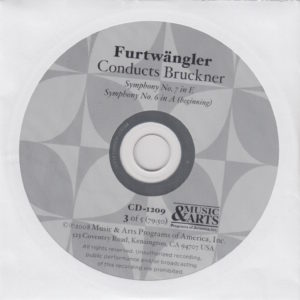

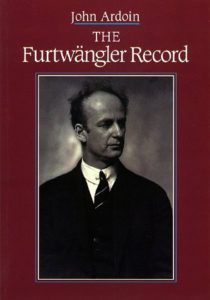

From the liner notes excerpted from John Ardoin’s book The Furtwangler Record (which I have, by the way; it’s an invaluable resource for Furtwangler fans):

Bruckner Symphony No. 7 in E major:

It has often been remarked that Bruckner’s final three symphonies are the culmination of his work as a composer in the magnitude of their scope, in the extension of traditional forms to contain his vast visions, and in the pervasive, dark colors he used. Yet in comparison to the Eighth and Ninth symphonies, the Seventh – arguably his most popular score – is remarkably forthright and untroubled.

Yet, as Furtwangler would surely have been the first to point out, how sublime the ideas are here, from the unearthly character of the opening theme (molded with shimmering, iridescent beauty) to the yearning strands of the adagio, the sharply cut motto of the scherzo, and the bounding exuberance that marks the germ of the finale.

Now, the objective stuff:

Bruckner’s Symphony No. 7 in E Major (WAB 107), composed 1881-1883

Bruckner’s Symphony No. 7 in E Major (WAB 107), composed 1881-1883

Wilhelm Furtwangler conducts

Furtwangler used the “1884-85 Gutmann Edition,” according to the liner notes.

Berlin Philharmonic plays

The symphony clocks in at 62:17

This was recorded in Cairo on April 23, 1951

Furtwangler 65 was when he conducted it

Bruckner was 59 when he finished composing it

This recording was released on the Music & Arts Programs of America label

Bruckner wrote his symphonies in four movements. The time breakdown of this one (Symphony No. 7 in E Major), from this particular conductor (Furtwangler) and this particular orchestra (Berliner Philharmoniker) is as follows:

I. Allegro moderato………………………………………………………………………………..19:16

II. Adagio. Sehr feierlich und sehr langsam…………………………………………..22:12

III. Scherzo. Sehr schnell………………………………………………………………………..09:47

IV. Finale. Bewegt, doch nicht schnell……………………………………………………11:42

Total Time: 62:17

Of the Gutmann edition, its entry on Wikipedia tells us,

Gutmann edition (published 1885)

Some changes were made after the 1884 premiere but before the first publication by Gutmann in 1885. It is widely accepted that Nikisch, Franz Schalk and Ferdinand Löwe had significant influence over this edition, but there is some debate over the extent to which these changes were authorized by Bruckner. These changes mostly affect tempo and orchestration.

Okay. Now, here are the subjective aspects:

My Rating:

My Rating:

Recording quality: 3 (lots of ambient sounds like coughing, shuffling)

Overall musicianship: 4

CD liner notes: 4 (thin booklet – in English only – that’s an excerpt from John Ardoin’s book The Furtwangler Record published in 1994)

How does this make me feel: 3

This was recorded in April of 1951 – some 66 years ago.

Do you know what the world was like back then?

Post World War II, just starting the Korean War…

Harry S. Truman was President of the United States.

Average income in America was $3,500.

Average price of a home in America was $7,300.

TV Shows that Debuted In 1951

Dragnet (January)

Search For Tomorrow (September)

I Love Lucy (October)

Hallmark Hall of Fame

Movies Released In 1951

Abbott and Costello Meet the Invisible Man (March)

An American in Paris opened in (August)

The Day the Earth Stood Still (September)

A Streetcar Named Desire (September)

The African Queen (December)

Popular Musical Artists in 1951

Rosemary Clooney

Tony Bennett

Perry Como

Nat King Cole

Mario Lanza

Louis Armstrong

They just don’t make ’em like that any more.

But what I’ve always loved about Classical music is that it virtually never changes. Sure, they don’t make Classical music like that any more, either. But we can play it today almost precisely as it was written hundreds of years previously.

Oh, it can sound different by recording technique, by conducting in a slightly different style. But we can play music written by Mozart today exactly the way he wrote it (give or take variances in instrument styles – period instrument versus modern) 300 years ago. Ditto for Bruckner. What we can play today – or as Wilhelm Furtwangler did in April of 1951 – is an extremely close approximation to what Anton Bruckner wrote in 1883.

That’s why Classical music can last forever – as long as people play instruments and appreciate the magic in the notes.

Singers? TV shows? Movies? Presidents? Music styles? They all come and go. (Surprisingly, Tony Bennett is still around; but none of the other ones are I noted above.) But Classical music stands the test of time.

This performance by Furtwangler is so-so. I’m not wowed by it, although as I sat at the bagel restaurant this morning listening to the first 25 seconds of the opening movement, I felt like the music was accompanying the sunrise. It’s precisely what Furtwangler historian John Ardoin noted above regarding the first movement: “unearthly character of the opening theme (molded with shimmering, iridescent beauty).” It felt like Furtwangler and his orchestra were bringing in the sunrise this morning.

The recording is so-so. The performance seems stellar. But I wasn’t rocked back on my heels by this interpretation of Bruckner’s Seventh.

Unless my ears deceived me, I could hear the crackles of an album (LP, vinyl) midway through the first movement – starting at 10:55 or so. When the orchestra quiets down, it sounds unmistakably like the music label for this release was recording from a vinyl album, rather than any extant master tapes. But I could be wrong.

NOTE: There is one niggling problem I have with the Furtwangler box set that I forgot to mention the first time I cracked it open: The paper sleeves the CDs come in are sealed.

Yes. Sealed.

Which means you have to tear them open to get the CD out.

Whose bright idea was that?

This box set was remastered very well, and – despite the goofy sealed CD sleeves – is an historic and sonic Must-Have for your collection.

Just my two cents.

Take it for what it’s worth.